NB: Cross posted from In Another Place, my professional blog

I have been fascinated with the Civil War since first seeing Ken Burns’ epic documentary. Moving to Virginia fueled that fascination, and I have visited many of the battlefields.

One of the most intriguing characters that came out of a war full of intriguing characters was Stonewall Jackson, an odd stiff man who seemed to only come into his own when in the midst of the war. Beyond the battlefield, he was unsuccessful in many ways. He often let his strong ethics get in the way of his relationships. His tenure in both the military and VMI was fraught with somewhat silly arguments with others. It was only when he found his place in the war that he began to shine as a strategist, warrior and, ultimately, a leader. After his death, even those in the north admired him for his tenacity and religious fervor. Abraham Lincoln, on reading a northern editorial about Jackson, wrote, “I sought my state-room, to weep there. Is it wrong, is it treason, to mourn for a good and great, though clearly mistaken man?” (p. 558). And, Henry Ward Beecher, ardent abolitionist and editor of The Independent, called Jackson, “Quiet, modest, brave, noble, honorable, and pure. He fought neither for reputation now, not for future personal advancement.” (p. 559).

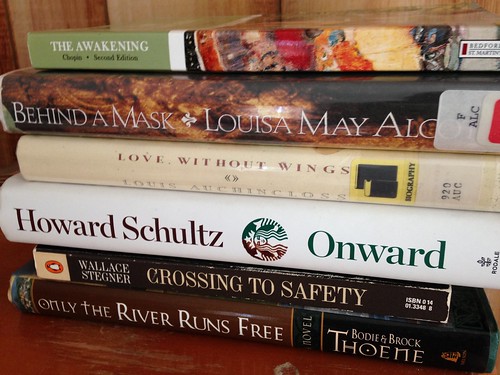

S.C. Gwynne‘s recent biography of Jackson, Rebel Yell: The Violence, Passion and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson, dissects the man, getting beyond the legend to reveal a loving husband and father and a loyal friend to those who get past the prickly exterior.

But Gwynne also highlights some essential leadership lessons that can be taken from Jackson’s life. One of those is the power of belief to drive men to do more or less than they might otherwise do. He speculates on why groups of soldiers might advance or retreat, writing:

Belief counted for a lot–in one’s general, in the caption in front of you brandishing his gleaming sword, in the bravery of one’s fellow soldiers, in the idea of winning itself…Though it is impossible to measure the effect of Jackson’s growing reputation as a winner on his men, it was undoubtedly strong (p. 321).

Often being a leader means having to influence people to do things they wouldn’t do naturally. When visiting the now peaceful battlefields, I find it unfathomable that soldiers on both sides, having witnessed the carnage of previous fights, were willing to continue to march into these battles. Yet, several times in Rebel Yell, Gwynne comments that the men of the Stonewall Brigade seemed, despite the deprivations and horror, happy as they followed the man who made them victorious against all odds. There is a lesson here for all of us who lead: build confidence by creating opportunities for success.